A boon and a curse – why a national reckoning with buffel grass is overdue: Richard Swain and Reece Pianta

July 11, 2025Richard Swain is an Invasive Species Council Indigenous Ambassador and Reece Pianta is the Invasive Species Council Advocacy Manager. Email contact: reecep@invasives.org.au

There are contrasting evaluations of buffel grass in Australia. Some farmers view it as an essential cattle feed, but its escape beyond grazing properties has created an ecological crisis. Indigenous communities, as articulated in the Umuwa Statement, experience buffel as a destructive weed, displacing native plants, intensifying bushfires, and endangering cultural heritage and health. Its aggressive spread creates the conditions for intense fires incinerating ancient trees, smothering water sources and displacing native vegetation. Buffel changes the profile of entire landscapes. A Weed of National Significance (WoNS) listing provides a framework to balance agricultural interests with the urgent environmental and cultural imperative to protect Country.

________________________________________________________________

For many graziers, buffel grass is a cornerstone of the pastoral economy – a hardy, fast-growing feed that tolerates harsh conditions, even in drought. In regions where rainfall is scarce and margins are tight, buffel has helped keep livestock fed and stations running.

But that’s only part of the story.

When buffel escapes the paddock and creeps across landscapes not meant for pasture, the very qualities that make it valuable become deeply destructive.

The Umuwa Statement, unanimously supported at the 2022 Indigenous Desert Alliance Conference, illustrates this contrast. The statement describes how buffel is ‘killing our country and threatening our communities and culture.’ This is the lived experience on Country where buffel presents as a weed by displacing native vegetation, intensifying bushfires, impacting cultural heritage and posing health risks.

Buffel grass isn’t just an invasive plant – it’s an ecological destroyer. It pushes out native grasses and wildflowers, smothers water sources, and fuels hotter, more destructive fires. In just 2 years, the Alinytjara Wilurara Landscape Board spent $925,000 – 17% of its budget – battling buffel alone. Perhaps most tragically, buffel fires are incinerating ancient river red gums – irreplaceable wildlife havens in Central Australia. The loss of these big old trees changes the topography of landscapes, altering erosion, water, fire and land management profiles. Buffel has the potential to change the nature of landscapes on Country in irreversible ways.

For many remote communities in rural Australia, buffel grass is not a boon; it is a curse. This is what has prompted the Northern Territory and South Australian governments to list it as a weed. Control work, particularly by Indigenous ranger groups, is eating into land management budgets. This is a region where people, equipment, materials and funding are already in short supply. The pressure only grows as buffel fires create a cycle, expanding buffel monocultures.

Benefits sought in WoNS listing

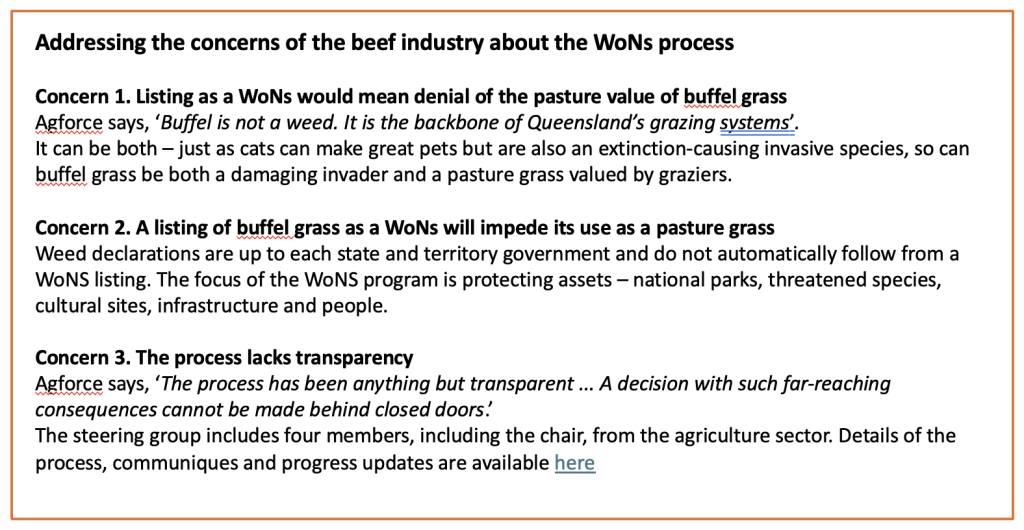

For some communities, buffel grass invasion is an emergency – a crisis threatening Country, culture and livelihoods. That’s why there’s a growing push to list it as a Weed of National Significance (WoNS). The goal is not to vilify or impede its use in grazing systems, but to support those battling its impacts beyond the farm gate. Yet some farming groups have interpreted the call as an attack on their way of life. It’s time to reset the conversation. Continuing with ad hoc, underfunded and fragmented management is no longer tenable. The WoNS framework offers a coordinated, practical path forward – one that recognises buffel’s value in pasture while confronting its damage elsewhere.

There is an ancient heritage of responsible custodianship of Country in Australia which continues to this day – and for the communities who signed the Umuwa Statement, buffel grass is already their weed of national significance.

A WoNs listing is our hope that people will come together to respectfully hear and answer the cry of Country. It will open the door for research, collaboration, planning for fire and landscape management. It will facilitate the conversation to come and support those already at work. It must begin with recognition of buffel grass as a national priority issue. From there, we need a clear plan to limit its spread, reduce its impacts, and marshal the resources needed to achieve this.

The different experiences of buffel are not mutually exclusive – but by listening to and understanding the range of community voices, we can find a way forward that protects the health of Country. It is clear we need strong processes to manage conflict species – this is an immediate area where we are in agreement with industry voices. Avoiding or delaying these decisions isn’t a solution. We should not exclude species from weed declarations or WoNS listings because of their commercial use in certain contexts. We need a system that effectively manages problems that escape these contexts. Governments should assess risks systematically and transparently, weigh all costs and benefits – environmental, cultural, social, economic – and make decisions that best serve Country and community.

The steering group includes four members, including the chair, from the agriculture sector. Details of the process, communiques and progress updates are available here (also see Ian Thompson’s submission in this newsletter).

Submitted: 8 July 2025

Categories

- Buffel grass Special Issue: Range Management Newsletter 25/2 (11)

- members area (11)

- News (35)

- Range Management Newsletter 15/2 (10)

- Range Management Newsletter 15/3 (12)

- Range Management Newsletter 16/1 (12)

- Range Management Newsletter 16/2 (9)

- Range Management Newsletter 16/3 (13)

- Range Management Newsletter 17/1 (15)

- Range Management Newsletter 17/2 (10)

- Range Management Newsletter 17/3 (12)

- Range Management Newsletter 18/1 (11)

- Range Management Newsletter 18/2 (13)

- Range Management Newsletter 18/3 (14)

- Range Management Newsletter 19/1 (15)

- Range Management Newsletter 19/2 (13)

- Range Management Newsletter 19/3 (11)

- Range Management Newsletter 20/1 (17)

- Range Management Newsletter 20/2 (20)

- Range Management Newsletter 20/3 (14)

- Range Management Newsletter 21/1 (17)

- Range Management Newsletter 21/2 (20)

- Range Management Newsletter 21/3 (21)

- Range Management Newsletter 22/1 (16)

- Range Management Newsletter 22/2 (17)

- Range Management Newsletter 22/3 (16)

- Range Management Newsletter 23/1 (16)

- Range Management Newsletter 23/2 (17)

- Range Management Newsletter 23/3 (14)

- Range Management Newsletter 24/1 (17)

- Range Management Newsletter 24/2 (14)

- Range Management Newsletter 24/3 (16)

- Range Management Newsletter 25/1 (12)

- Range Management Newsletter 25/3 (14)